Autorin: Berit Warta

In the modern Western World, studying the atlas is a crucial part of geography class. Opening the collection of maps, we let our eyes scan the pages, we let the index finger trace the amazon river, the mind wanders between bubbling volcanoes in Finland, we stand at the foot of the Himalayas and look nine kilometres up. We are familiar with the atlas, aware of its peculiarity that makes us daydream travel, using the equator as a hula hoop, dancing around the globe without any limitation. Its ultimate purpose lies in locating one’s place within an environment, as well as making sense of the geopolitical, social, religious and economic spheres within.

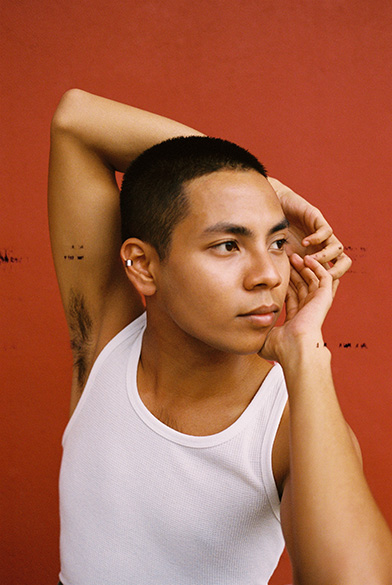

As a former servant of the military and combat photographer, Hidhir Badaruddin might have studied more maps than others, sharpening his sense of orientation. Still, growing up as a queer, brown Asian in Singapore, the media landscape made it difficult for him to track down the place that says: ‚I can see you – this is where you belong!‘ Just as if the atlas’ creators had forgotten to create space for his community at all. The issue of underrepresentation of brown Asians and queer identities leaves people like Hidhir often lost and struggling with stereotypes. But while the compass spins in endless turns, Hidhir put his finger on it. He decided the place to start and make a change is everywhere he is. Through sharing his experience and telling stories through his photography he is changing the visual media narrative – aiming to normalise the presence of Asian identities of different origins and sexualities in the media cosmos. In 2020, the London College of Fashion graduate went viral with his photo series Younglawa, capturing the multiplicity of Asian masculinity and the diversity of Asian heritage. His vision makes him one of the disruptors, constructing a more inclusive and diverse industry for everyone, everywhere.

FT: Younglawa, can you tell us a bit about growing up in Singapore and moving to London?

Younglawa: „About three years ago I moved to study Creative Direction at London College of Fashion. Before that I was actually in the army. In Singapore, you must serve in the military, that’s mandatory for all males. As much as I did not want to do it, I kind of knew from a young age that at some point I will have to do it. Anyway, I think I have always been into photography. Even in the army. I took over the role of combat photographer when the opportunity came up. Then I moved to London and in uni, I started doing test shoots, had my first publication with Gay Times magazine, where I shot five male trans models and in my final year at the end of 2019, I started my series Younglawa.“

What does Younglawa mean?

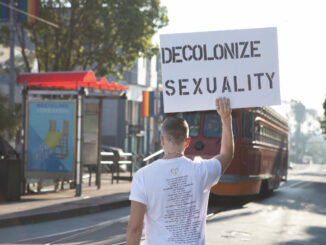

„It is a play on words in English and Malay. I thought it would be nice to introduce both. In Malay Younglawa literally means something that is beautiful or someone that is beautiful. I had this idea for a couple of years already because I think being in London made me view the things I had back home and took for granted in a different light. What does back home sound or smell like? I would describe my home, Singapore, as being very colourful. It is diverse in the sense of it is a mix of people, very multi-racial. You get different kinds of food everywhere.I grew up with that kind of mix but when you grow up with it you don’t see it as something special. Coming here made me realise I miss the food and messiness of different cultures being together. But as much as it is colourful, it is still backward in a sense of LGBTQ rights – which are non-existent. That’s an issue very much not spoken about. I grew up not seeing representation of queer people. You don’t see the colourfulness in gender expression diversity. There was no outlook. My outlook was through magazines like Dazed & Confused or i-D. I also saw more representation through Western media than my own local media back home. Talking about media representation in Singapore – it was still very much like lighter skin and fair skin people being more favored in media.“

Some friends from Malaysia made me aware of the popular skin-lightening products huge companies put out there. They offer products, creating a kind of dangerous desire…

„Colourism does exist! Even in the Asian community where lighter skin tones are favoured. This means Chinese or Korean or any lighter people were more present in the media. But this made me realise I want to change the visual narrative. I created my series Younglawa because I wanted to show there is more diversity and a wider spectrum of Asian identities within the Asian community. There are Indian, Pakistanis, Malays, Filipinos and I think people forget. The idea for the series was triggered when I was at a house party in London. Someone I was talking to asked me: “Oh what kind of Asian are you?” and I answered: “I am Indian and Malay”. The persons were reacting kind of confused. They did not want to tell me, but I could tell in a sense that they might only see a lot of people from China, Japan or Korea. However, what you see in fashion, at Versace for example, is that brands try introducing more diversity through Asian and black models. But when you see the Asian models – they are all very fair skin. Darker skin people are never really given that platform and this is what I wanted to tackle with Younglawa. But obviously, the series got cut short because of Covid. I was lucky that I shot four or five boys when I was in Singapore in December 2019.“

No stereotype!

How did you feel after the situation at the house party?

„Obviously, I was taken a bit aback. But, I immediately put myself in their shoes, imagining they might have not been exposed to a diverse community growing up. Afterward I thought that what I do is visual and everything you see you see on social media or the television influences the way you think and the way you see life. So, working in media anyway I saw the opportunity to change the narrative visually. With Younglawa, I want to show that there is a wider spectrum of diversity within the Asian community because I think a lot of people are just thinking about Asian people by one look. People always think I am Hawaiian for example. I felt like there is space for the series. And even though it never got finished, Dazed and Face magazine picked it up. That really opened my mind to explore this further. I am now actually in the works of creating a book and making an exhibition for Younglawa. Maybe in a year’s time. I don’t want to rush the process. And also because I got the £10k Getty Images Grant which I did not see coming. So, this opened my eyes and made me realise, there is something here, people seeing something in your work.“

Do you feel personally responsible to push for more visibility for brown Asians?

„Oh yes! It was definitely more like the responsibility developed. I knew it was important but I realised HOW important it is when I got messages from people from the Philippines and Indonesia, some random direct messages on Instagram because people came across articles online and messaged me, saying they felt glad to be represented in a way they have not been before. Now I start to feel the pressure, because I want to do it really well.“

What you created is very much like making people aware of a red traffic light that has always been there but has just been ignored.

„Yes! I was talking to some people within photography about the photographer Ren Hang and realised that his work was the go-to for Asian representation and Asian masculinity. When you see Ren Hang’s pictures, they are very much one look of Asians. He captured people from where he is from, which is China, and to me, the people are photographed in a not very strong, a bit weak, maybe a bit more fragile way. I do not want to live up to the stereotype.“

What makes you feel like belonging and secure?

„Doing photography! I know this is very cliché but creating images that I have in my head – this is what makes me feel very comfortable. It makes me feel secure, but at the same time this security comes with insecurity because what you are creating has consequences.“

Style & the Gang X FASHIONTODAY MEN

We cooperate! This article was written in cooperation with the international platform for ethical fashion www.styleandthegang.com. Whether from Tokyo, Kilifi, Barcelona or Bali – on their website the editors Tays Jennifer Köper-Kelemen and Nina Elyas present unusual, socially committed and ethical fashion brands with cross-cultural concepts from all over the world. Curated designers tell their stories of craftsmanship, and what it means to create fashion with added value.